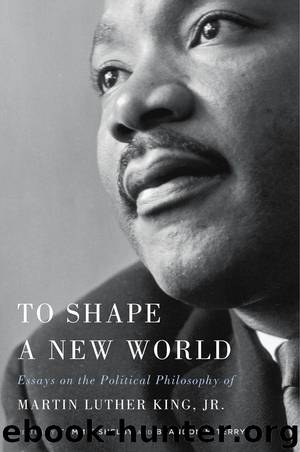

To Shape a New World by Tommie Shelby & Brandon M. Terry

Author:Tommie Shelby & Brandon M. Terry

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Harvard University Press

11

Living “in the Red”: Time, Debt, and Justice

LAWRIE BALFOUR

Whether we realize it or not, each of us lives eternally “in the red.” We are everlasting debtors to known and unknown men and women.

—MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR., Where Do We Go from Here

Democracy, in its finest sense, is payment.

—MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR., Why We Can’t Wait

“In the Red”

We are indebted, Martin Luther King, Jr., contends, to the labor and ingenuity of people around the world and to the work of generations bound together in an economy that is moral as well as commercial. King’s claim is familiar to anyone who has spent time with his words and political example. The entanglement of every nation and each individual life with every other is a keystone of his thinking, from the Montgomery movement until his death in 1968. If there is nothing surprising about King’s intimation that such connectedness spans historical eras as well as national boundaries, however, his formulation does more than reaffirm human beings’ mutual interdependence. It joins King’s understanding of justice to a philosophy of history in which today’s generation is doubly indebted to generations past and yet to come. King’s account of what it means to be “in the red” is also doubled in another sense. Even as he insists on the universalism of our indebtedness, thereby drawing all of his readers into a shared sphere of responsibility, King makes particular note of the debts, still unpaid, for what another great orator called “the wealth piled by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil,” for “every drop of blood drawn with the lash,” and for the century of exploitation and violent suppression that followed the Civil War. Looking back at this bloody history, King departs from Lincoln when he concludes that “the practical cost of change for the nation up to this point has been cheap.”1 Looking ahead, he urges his readers to reckon with unpaid bills, domestic and global, at once, or risk losing everything we value.

Although King rejects any politics based narrowly on interest, financial metaphors and critiques of unjust economic arrangements pervade his political writings. Perhaps the most famous example is his 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech, in which he speaks of traveling to Washington “to cash a check,” to demand the fulfillment of the “promissory note” embodied in the Declaration of Independence.2 Economic language, if less pronounced, also emerges in his earlier work. In Stride toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story (1958), for example, King decries “an essentially unreconstructed economy” that has preserved the exploitation of African Americans from emancipation to King’s own time.3 And it persists through King’s posthumously published “A Testament of Hope,” where he prophesies that “justice so long deferred has accumulated interest and its cost for this society will be substantial in financial as well as human terms.”4 Crucially, King departs from pure economic logic, insofar as he insists on the distinction between just and unjust transactions. The view that African Americans must pay for their basic rights, he argues, is unjust.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12391)

The handmaid's tale by Margaret Atwood(7763)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(7346)

Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking by M. Neil Browne & Stuart M. Keeley(5774)

Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear by Elizabeth Gilbert(5771)

Ego Is the Enemy by Ryan Holiday(5445)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(5096)

On Writing A Memoir of the Craft by Stephen King(4942)

Ken Follett - World without end by Ken Follett(4731)

Adulting by Kelly Williams Brown(4574)

Bluets by Maggie Nelson(4555)

Eat That Frog! by Brian Tracy(4536)

Guilty Pleasures by Laurell K Hamilton(4448)

The Poetry of Pablo Neruda by Pablo Neruda(4106)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(4031)

White Noise - A Novel by Don DeLillo(4009)

Fingerprints of the Gods by Graham Hancock(4004)

The Book of Joy by Dalai Lama(3986)

The Bookshop by Penelope Fitzgerald(3852)